Source material

- S. Russell, P. Norvig (2021) - Chapter 2

| Next topic >>

Agents and Environments

DEF - Agent

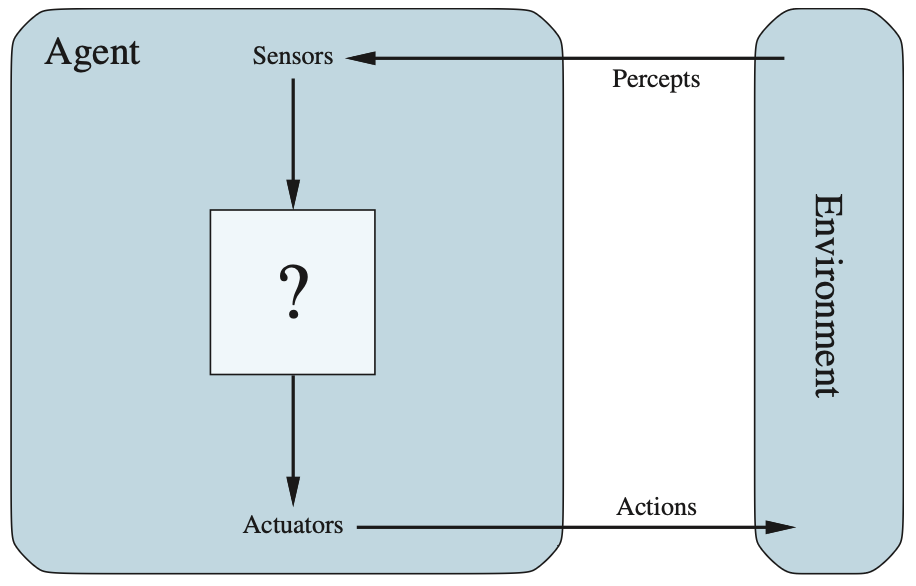

An agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators. We use the term percept to refer to the content an agent’s sensors are perceiving. An agent’s percept sequence is the complete history of everything the agent has ever perceived.

This simple idea is illustrated in the following diagram.

Taken from S. Russell, P. Norvig (2021)

Taken from S. Russell, P. Norvig (2021)

In general, an agent’s choice of action at any given moment can depend on its built-in knowledge and the entire percept sequence observed so far, but not on anything it hasn’t perceived. By specifying the agent’s choice of action for every possible percept sequence, we have essentially defined the agent’s behavior. Mathematically, an agent’s behavior is described by the agent function, which maps any given percept sequence to an action.

We can imagine tabulating the agent function for any given agent. For most agents, this would result in a very large table—infinite, in fact, unless we limit the length of percept sequences under consideration. Given an agent to experiment with, we could, in principle, construct this table by testing all possible percept sequences and recording the agent’s responses. The table is an external characterization of the agent.

Internally, for an artificial agent, the agent function is implemented by an agent program. It is important to distinguish between these two concepts:

The agent function is an abstract mathematical description, while the agent program is a concrete implementation running within a physical system.

Rationality

Moral philosophy has developed several different notions of the “right thing,” but AI has generally stuck to one notion called consequentialism: we evaluate an agent’s behavior by its consequences. When an agent is plunked down in an environment, it generates a sequence of actions according to the percepts it receives. This sequence of actions causes the environment to go through a sequence of states. If the sequence is desirable, then the agent has performed well.

This notion of desirability is captured by a performance measure that evaluates any given sequence of environment states.

Humans have desires and preferences of their own, so the notion of rationality as applied to humans has to do with their success in choosing actions that produce sequences of environment states that are desirable from their point of view. Machines, on the other hand, do not have desires and preferences of their own; the performance measure is, initially at least, in the mind of the designer of the machine, or in the mind of the users the machine is designed for. Some agent designs have an explicit representation of (a version of) the performance measure, while in other designs the performance measure is entirely implicit—the agent may do the right thing, but it doesn’t know why.

What is rational at any given time depends on four things:

- The performance measure that defines the criterion of success.

- The agent’s prior knowledge of the environment.

- The actions that the agent can perform.

- The agent’s percept sequence to date.

This leads to a definition of a rational agent:

DEF - Rational Agent

For each possible percept sequence, a rational agent should select an action that is expected to maximize its performance measure, given the evidence provided by the percept sequence and whatever built-in knowledge the agent has.

Rationality vs omniscience

Rationality differs from perfection. Rationality maximizes expected performance, while perfection maximizes actual performance. Expecting an agent to always take the best action after the fact is impossible without omniscience or tools like crystal balls or time machines.

Rationality relies on the agent’s percept sequence up to the present moment, not future knowledge. For example, if an agent doesn’t look before crossing a road, it risks making a poor decision without full information. Rational agents should gather information, like looking before crossing, to improve performance.

Information gathering and learning from experience are essential aspects of rationality. While prior knowledge can guide the agent, it must adapt its knowledge based on new percepts. In fully predictable environments, however, the agent doesn’t need to learn or perceive—it just acts.

Autonomy

An agent that relies heavily on its designer’s prior knowledge rather than its own percepts and learning processes lacks autonomy. A rational agent should strive for autonomy by learning to compensate for partial or incorrect prior knowledge.

However, complete autonomy isn’t needed right away. Initially, an agent may require guidance from the designer, much like animals rely on built-in reflexes to survive until they can learn. Over time, as the agent gains more experience, its behavior can become independent of prior knowledge. Learning enables the creation of a single rational agent capable of succeeding in a wide range of environments.

The nature of Environments

With a definition of rationality, we can start thinking about building rational agents. However, first, we need to define task environments, which are the “problems” that rational agents are designed to solve. The nature of the task environment significantly influences the appropriate agent design.

Task environments

In specifying the task environment the following are needed:

- Performance measure

- Environment

- Actuators

- Sensors

which go under the acronym PEAS.

Task environments in AI can be categorized along a fairly small number of dimensions which help determine the appropriate agent design and the techniques for implementation.

Fully and partially observable environments

- Fully observable: The agent’s sensors provide complete access to the environment at all times. The agent does not need to maintain internal state.

- Partially observable: Sensors may be noisy, inaccurate, or missing relevant state data. For example, a vacuum agent with a local dirt sensor or a taxi unable to perceive what other drivers are thinking.

- Unobservable: An agent has no sensors at all. However, some goals may still be achievable even in this case.

Single-agent and multiagent environments

- Single-agent: The agent operates alone, like solving a crossword puzzle.

- Multiagent: There are multiple agents, such as in a game of chess.

- Competitive multiagent: Agents work against each other, e.g., in chess, where one agent’s success reduces the other’s performance.

- Partially cooperative multiagent: In scenarios like taxi-driving, avoiding collisions benefits all agents, but competition arises, e.g., when fighting for a parking spot.

Multiagent environments introduce challenges like the need for communication or randomized behavior to avoid being predictable.

Deterministic and Nondeterministic environments

- Deterministic: The next state of the environment is fully determined by the current state and the agent’s action.

- Nondeterministic: The environment is not entirely predictable, often due to complexity or unobserved aspects.

- Stochastic: Similar to nondeterministic but deals with quantitative probabilities.

An Example: Taxi driving is nondeterministic due to unpredictable traffic and potential mechanical issues.

Episodic and Sequential environments

- Episodic: The agent’s experience is divided into independent episodes where past actions do not affect future ones.

- Sequential: Current actions affect future decisions; examples include chess and taxi driving.

- Episodic environments are simpler as agents don’t need to plan ahead.

Static and Dynamic environments

- Static: The environment does not change while the agent is deliberating.

- Dynamic: The environment changes continuously, requiring the agent to keep up with it.

- Semidynamic: The environment remains unchanged, but the performance score changes over time (e.g., chess with a clock).

Discrete and Continuous environments

- Discrete: The environment has a finite set of states and actions (e.g., chess).

- Continuous: The environment involves smooth transitions over time (e.g., taxi driving with continuous changes in speed and position).

Known and Unknown environments

- Known: The agent/designer knows the laws of physics of the environment.

- Unknown: The agent must learn how the environment works to make good decisions. This is distinct from observable environments; an environment can be known but partially observable or unknown but fully observable.

- Performance measure uncertainty: In some cases, the performance measure may be unknown, requiring the agent to learn through interactions with the user or designer (e.g., a taxi driver learning passenger preferences).

The structure of Agents

So far, we have discussed agents in terms of their behavior—the action performed after any given sequence of percepts. Now, we need to examine how their internal mechanisms work.

The goal of AI is to design an agent program that implements the agent function, which maps percepts to actions. This program is assumed to run on a computing device with physical sensors and actuators, referred to as the agent architecture:

The key challenge for AI is to find out how to write programs that, to the extent possible, produce rational behavior from a smallish program rather than from a vast table.